This striking building, which dates from about 1906, was designed by W. A. (for William Arthur) Thomas, a prolific architect and developer who is almost forgotten today. It’s time for a Thomas revival, Father Pitt thinks, because wherever he went, Thomas left the city more beautiful and more interesting.

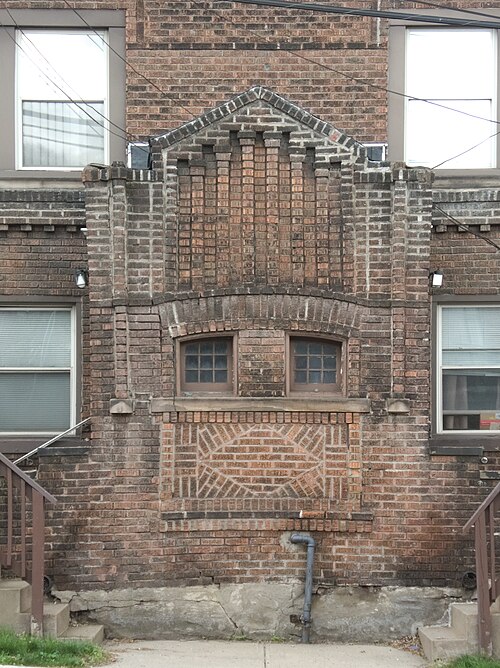

The most attention-getting part of this building is the tower of half-round balconies in the front, and here the design is amazingly eclectic. Corinthian capitals on the pilasters and abstract cubical capitals on the columns—and then, on the third floor, tapered Craftsman-style pillars. But we don’t see a disordered mess. It all fits together in one composition.

Now, it’s possible that the interesting mixture of styles was the product of later revisions. But we are inclined to attribute an experimental spirit to Mr. Thomas. At the other end of the block…

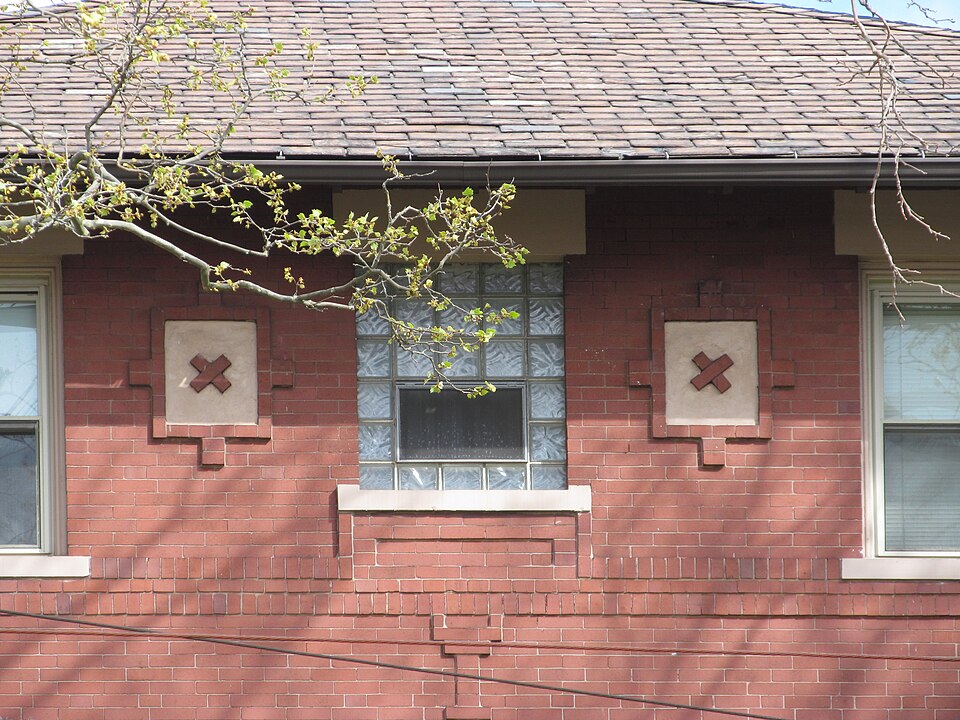

This building is so similar that we are certainly justified in attributing it to Thomas as well unless strong evidence to the contrary comes in. But it is not identical. Here the columns go all the way up, and they terminate in striking Art Nouveau interpretations of classical capitals.

Volutes and acanthus leaves are standard decorations for classical capitals, but the proportions and the arrangement are original.

A fourth floor of cheaper modern materials has been added, but the addition was deliberately arranged to be unobtrusive, or indeed almost invisible from the street. Most passers-by will never even notice it.

Comments