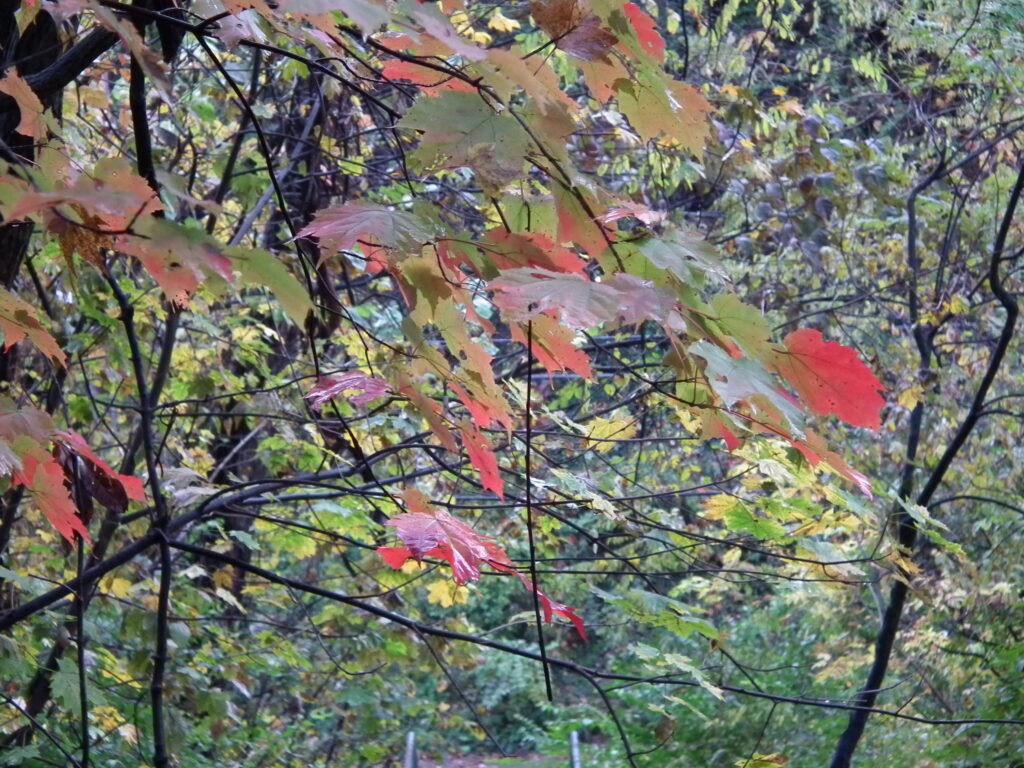

Father Pitt usually thinks of the photograph as the raw material for a picture, meaning that the photograph will go through a good bit of adjustment before he publishes it. But every once in a while, he challenges himself to publish pictures directly from the camera. On this expedition, he also focused all the pictures manually, just to see how good the Fujifilm FinePix HS10 was at manual focusing. Pretty good.