Rooftops of houses on the South Side Slopes, with Oakland and its usual cranes in the background.

Rooftops of houses on the South Side Slopes, with Oakland and its usual cranes in the background.

St. Paul of the Cross, founder of the Passionists, was an Italian, and the architect John T. Comès gave the Passionists on the Slopes a bit of Italy to live in.

A Passionist monastery is called a “retreat,” but the neighbors just call this one a monastery: the streets around it are Monastery Street, Monastery Place, and Monastery Avenue.

A later addition is in quite a different style.

This is the edge of the section locals call Billy Buck Hill, the bulge in the Slopes enclosed by a long loop of South 18th Street. These houses along South 18th Street were built shortly before 1910, according to old maps; they are a little grander than some of their neighbors behind them, and they are good exercises in urban archaeology. Not one of them is in original condition, but we can probably reconstruct what they looked like when they were new by comparing the houses.

First, four out of the five share a blank spot in the wall above the front door that seems unusual. You would expect a window there. The fifth has a window, though it’s an odd oval shape. Nevertheless, that oval window appears to be original. We can tell nothing from the third and fourth houses in the row, which have had their entire fronts replaced with fake stone, but a close look at the first and second houses (enlarge the picture to examine them) shows that the bricks in the front walls have been filled in just where such a window would be, and in a roughly oval shape.

That projecting second-floor window on the fifth house is also unusual, but here old Pa Pitt is inclined to say it is probably not original. It looks like a local contractor’s more modern renovation. The second house is probably the only one that preserves the original shapes of its windows upstairs and downstairs, although the windows themselves have been replaced.

All the dormers have been renovated in various ways, but the ones on the first and fifth houses may be closest to what all the dormers originally looked like.

The first and fifth houses also preserve their original chimneys. Two of the others have lost their tops, and the chimney on the third house has been rebuilt from the same stone substitute that was used for the front.

Three of the houses have aluminum awnings. The ones on the second and third houses are genuine Kool-Vent.

This has the look of a “hotel” in the Pittsburgh sense: a bar with rooms upstairs, thus qualifying for the much more readily available hotel liquor license. It still has a bar on the ground floor. The style is what old Pa Pitt calls “South Hills German Victorian,” and indeed a glance at the plat maps shows that this part of the Slopes was thoroughly German when this building went up shortly before 1910. The whole triangle bounded by South 18th Street, Monastery Place, and Monastery Street (now Monastery Avenue) was owned by Elizabeth Lenert.

When your building has an acute angle, but not sharply acute, one way of dealing with it is to put the entrance there and make the corner into a feature rather than something that looks like an unfortunate necessity. The rocket-shaped turret on this building acts like a hinge to make it feel as though the building was meant to fold into this shape.

Otherwise, this is not an elaborate building, but the clever arrangement of bricks at the top of the 18th Street side makes an attractive cornice that doesn’t fall down.

We must pause to admire two different chimney pots, both of them fine examples of their types.

The building would have had a much more dignified and balanced appearance before the ground-floor storefront was filled in; but since a corner bar is close in spirit to a men’s club, patrons should be grateful that it has windows at all.

It seems certain that this building, formerly the girls’ school for St. Michael’s parish, will be demolished sooner or later; what has saved it so far is the expense of demolishing a large building in a neighborhood with low property values. But the South Side Slopes, like many city neighborhoods, have become much more valuable lately.

Right now, the building appears to house a whole alternate civilization of “homeless” squatters. In an ideal city, perhaps, it could continue to do so, but with a city budget for maintaining it and providing the elementary comforts to the residents. We do not live in that ideal city.

At any rate, it seemed worth stopping to record a few details of the building before it disappears entirely, and another piece of Pittsburgh’s rich German history is gone. We also have a few pictures from a year and a half ago, including a composite view of the front.

“St. Michael’s Mädchen Schule” (“St. Michael’s Girls’ School”).

“Errichtet A. D. 1872” (“Erected A. D. 1872”).

“Wiedererbaut A. D. 1900” (“Rebuilt A. D. 1900”).

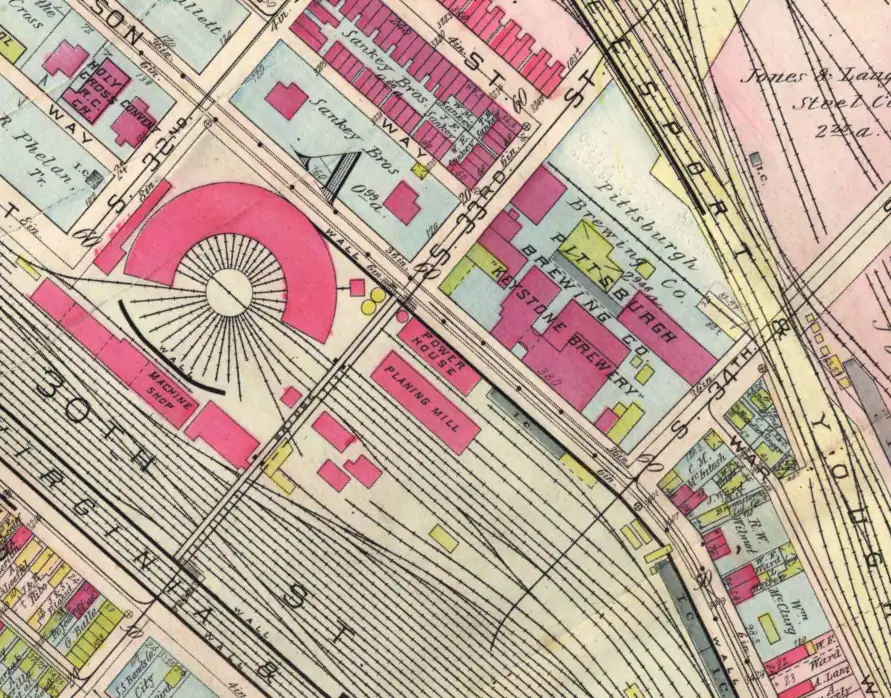

To the south, at the base of the steep South Side Slopes, was a small but crowded neighborhood of workmen and their families. To the north was a huge steel mill, a railroad roundhouse and shops, and a big brewery. In between was a railroad yard with more than twenty tracks to cross. How would the workmen get to work without getting run over by switching locomotives every day? The answer was to extend 33rd Street from the Slopes to the Flats as a pedestrian tunnel under the main line, followed by a long pedestrian bridge over the railroad yards.

The bridge and the railroad yard are gone now; the tunnel remains, but since it goes nowhere it is blocked. The tunnel entrance is still attractive in its stony simplicity.

St. Josaphat’s is one of the most unusual of John T. Comès’ works. It has some of his trademarks, notably the stripes—he loved stripes. But it also takes more inspiration from Art Nouveau than most of his churches, which are usually more firmly rooted in historical models. It is now having some renovation work done to fit it for its post-church life.

Imagine the uproar that would ensue if your city government today decided to hire a Beaux-Arts master like Thomas Scott to design a monumental palace for such a utilitarian purpose as a water-pumping station. Imagine the inquiries that would probe the vital questions of how much each of those carved faces cost and why stone trim was used when the same object could be accomplished with aluminum. The world has made a lot of progress since Scott, architect of the Benedum-Trees Building downtown (where he kept his architectural office, naturally), gave us this $100,000 pumping station on an out-of-the-way street on the South Side Slopes.1

There were doubtless security reasons for bricking in the towering windows that used to flood the place with light. But Father Pitt cannot help suspecting that the real reason is that the workers here constituted a sort of men’s club, and men’s clubs in Pittsburgh abhor natural light.

Even in November, much of the building is obscured by trees.