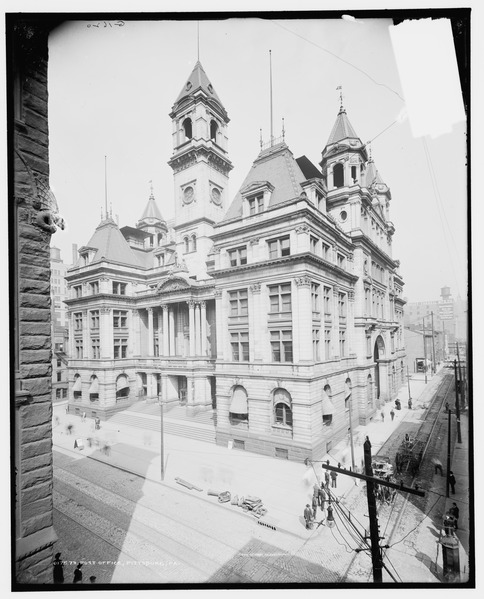

When the new Post Office and Federal Building was designed in 1889 (it opened in 1892), the sculptor Eugenio Pedon, who had the franchise for decorating federal buildings, contributed two identical groups of allegorical statues to go over the entrances: Navigation, Enlightenment, and Industry. When the building came down in 1966, the groups were rescued and split up. One set of Navigation and Enlightenment ended up here at Allegheny Center, where they’re known as the Stone Maidens.

The old Post Office and Federal Building. If you enlarge the picture, you can see the Pedon statues above the entrance at the fourth-floor level.

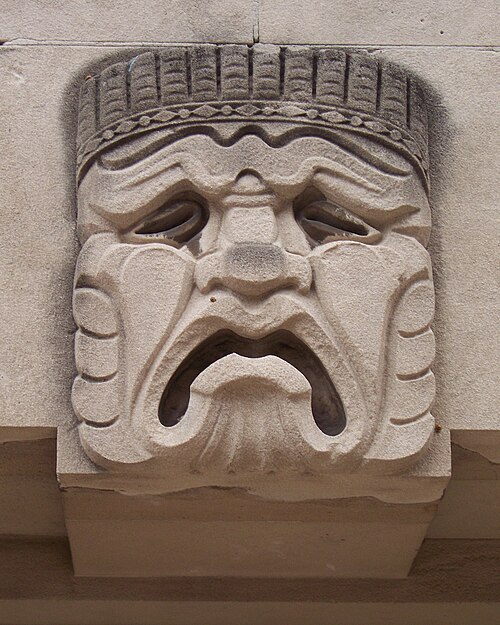

Navigation. If the faces and bodies seem disproportionately elongated, remember that we are meant to be looking up at them from far down in the street; the sculptor adjusted his perspective accordingly.

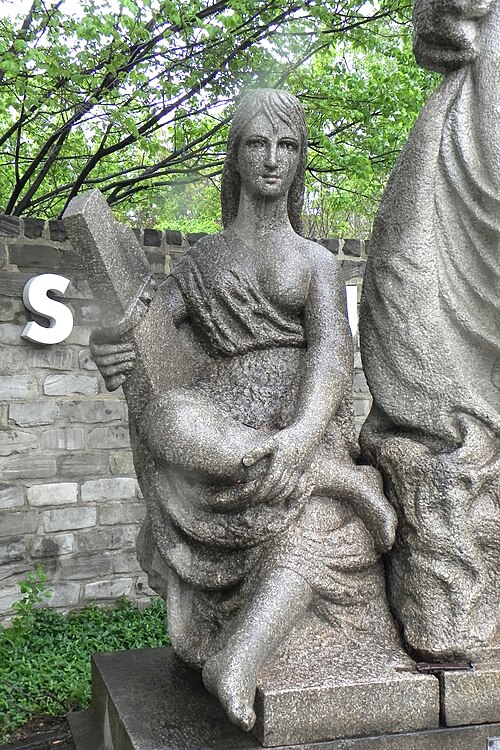

Enlightenment. The twin statue of Enlightenment ended up at the corner of a Rite Aid parking lot on Mount Washington. Below we see her trying to hold back the clouds of darkness, which goes as well for her as it always does.

One of the statues of Industry ended up at Station Square, and old Pa Pitt will try to remember to get her picture soon and complete the set.

Comments