Twilight views of West Park on the North Side, with snow covering the frozen Lake Elizabeth.

The Civil War monument.

Comments

Twilight views of West Park on the North Side, with snow covering the frozen Lake Elizabeth.

The Civil War monument.

Commercial electric light was only a few years old when this power station was built in 1889. It was built in a restrained Victorian classical style that seems meant to make electric power look tame and respectable. But just a few years later, a new building was added next door that conveys quite a different architectural message.

The Irwin Avenue Substation was built in 1895, but it has the look of something built shortly after the Norman Conquest. The architectural message here seems to be that electricity is such a mighty force that only a medieval fortress can keep it under control. This building still belongs to Duquesne Light, and it is still called the Irwin Avenue Substation, even though Irwin Avenue has been called Brighton Road for more than ninety years.

When the new Post Office and Federal Building was designed in 1889 (it opened in 1892), the sculptor Eugenio Pedon, who had the franchise for decorating federal buildings, contributed two identical groups of allegorical statues to go over the entrances: Navigation, Enlightenment, and Industry. When the building came down in 1966, the groups were rescued and split up. One set of Navigation and Enlightenment ended up here at Allegheny Center, where they’re known as the Stone Maidens.

The old Post Office and Federal Building. If you enlarge the picture, you can see the Pedon statues above the entrance at the fourth-floor level.

Navigation. If the faces and bodies seem disproportionately elongated, remember that we are meant to be looking up at them from far down in the street; the sculptor adjusted his perspective accordingly.

Enlightenment. The twin statue of Enlightenment ended up at the corner of a Rite Aid parking lot on Mount Washington. Below we see her trying to hold back the clouds of darkness, which goes as well for her as it always does.

One of the statues of Industry ended up at Station Square, and old Pa Pitt will try to remember to get her picture soon and complete the set.

A few months ago Father Pitt published a view of the front of the old Presbyterian Hospital on the North Side, which is where Presby lived before it moved to Oakland to become the nucleus of the medical-industrial complex there. Since he was walking by the building again the other day, old Pa Pitt thought he would add a few more details.

Addendum: The architect was C. C. Badgley of Fairmont, West Virginia, whose plans were chosen from among several submitted by local architects.1

After Presby moved out, this site was used as Divine Providence Hospital for many years. The last we heard, the building was mostly vacant, but was being considered for conversion to “affordable” apartments.

We can just make out the ghosts of letters spelling out “DIVINE PROVIDENCE HOSPITAL.”

If we cannot find a use for a building, Mother Nature will.

Andrew Peebles was the architect of St. Peter’s, which was dedicated in 1874. In 1876, it became the cathedral of the new Roman Catholic Diocese of Allegheny, carved out of the Diocese of Pittsburgh, which was left with all the debt while the new Diocese of Allegheny took all the rich churches. That went about as well as you might expect, and in 1889 the Diocese of Allegheny was suppressed and its territory reabsorbed by Pittsburgh. But a church never quite gets over being a cathedral.

In 1886, a fire ravaged the building and left nothing but the walls standing. Fortunately Peebles’ original plans were saved, and so the restoration, which took a year and a half, was done to the original design.

The rectory was built with a stone front to match the church, but the rest of the house is brick.

We also have a picture of the front of St. Peter’s at night.

Allegheny High School, now the Allegheny Traditional Academy, has a complicated architectural history involving two notable architects at three very different times.

The original 1893 Allegheny High School on this site was designed by Frederick Osterling in his most florid Richardsonian Romanesque manner. This building no longer exists, but the photograph above gives us a good notion of the impression it made. The huge entrance arch is particularly striking, and particularly Osterling; compare it with the Third Avenue entrance of the Times Building, also by Osterling.

In 1904, the school needed a major addition. Again Osterling was called on, but by this time Richardsonian Romanesque had passed out of fashion, and Osterling’s own tastes had changed. The Allegheny High School Annex still stands, and Osterling pulled off a remarkable feat: he made a building in modified Georgian style that matched current classical tastes while still being a good fit with, and echoing the lines of, the original Romanesque school.

The carved ornaments on the original school were executed by Achille Giammartini, and we would guess that he was brought back for the work on the Annex as well.

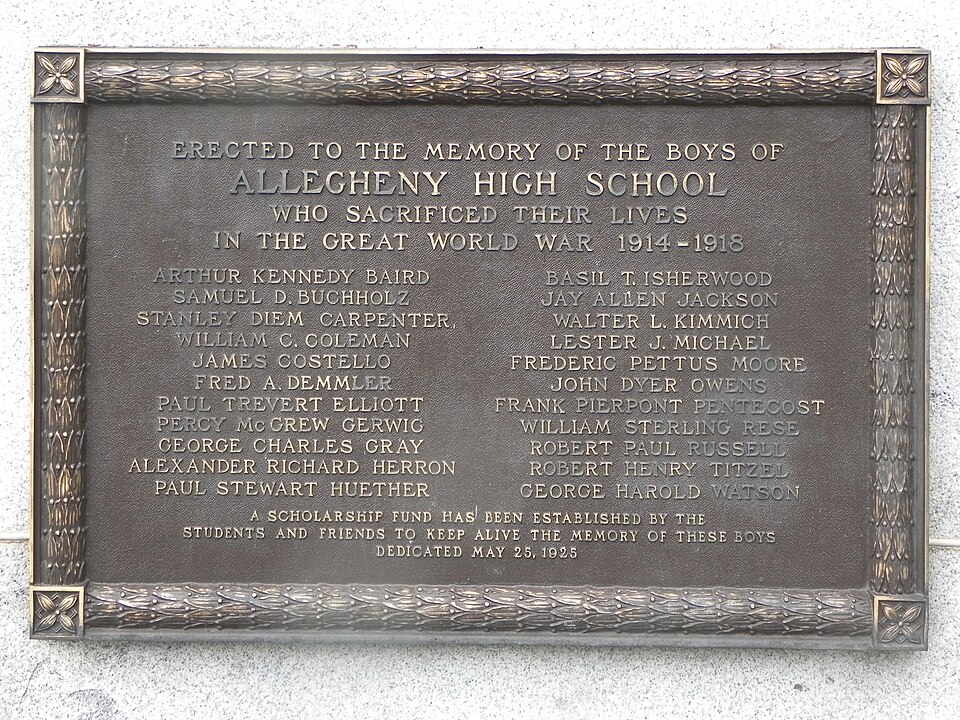

A war memorial on the front of the Annex. Twenty-two names are inscribed. Everyone who went to Allegheny High in those years knew someone who was killed in the Great War.

By the 1930s, the school was too small again. The original school was torn down, and Marion Steen, house architect for Pittsburgh Public Schools (and son of the Pittsburgh titan James T. Steen) designed a new Art Deco palace nothing like the remaining Annex. The two buildings do not clash, however, because there are very few vantage points from which we can see both at once.

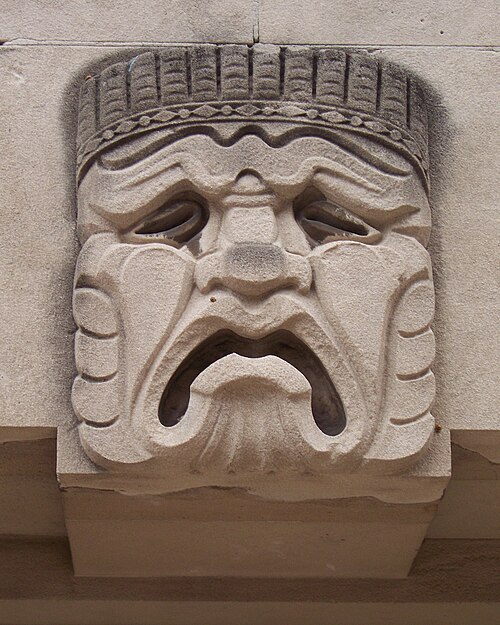

The auditorium has three exits, each one with one of the three traditional masks of Greek drama above it: Comedy, Meh, and Tragedy.

International Harvester was a big maker of farm equipment, but also of trucks and sport utility vehicles before anyone knew that they were sport utility vehicles. This was the company’s facility in Pittsburgh, built right on the railroad near the North Side yards.

Fortunately the building was never abandoned—it later became the headquarters of the Harry Guckert Company—so that it was in good structural shape when it was converted to loft apartments about two years ago, as we read in this article at Next Pittsburgh. The building is now on the National Register of Historic Places. According to a draft of the nomination, the architect was August C. Wildmanns.

Map.

Lake Elizabeth in West Park on the North Side. Above, just a few weeks ago. Below, in 1999.

Built in 1906, this was the main building of Presbyterian Hospital until it moved to vastly larger facilities in Oakland in the 1930s. The building was later part of Providence Hospital, and now is used for offices.

Arch Street, which is now included in the Mexican War Streets despite not bearing the name of a battle or a general, is a typical North Side combination of dense rowhouses, small apartment buildings, and backstreet stores. Here are just a few sights within one block of the street.

An exceptionally elaborate Queen Anne house whose owner has used bright but well-chosen colors to emphasize the wealth of detail on the front.

Two modest houses from before the Civil War; the brick house at left is dated 1842.

A small apartment building with a well-balanced classical front.

Some fine woodwork surrounds a front door.

The colorful dormer steals the show, but enlarge the picture to appreciate the terra-cotta grotesques on the cornice.

This little building looks as though it dates from the 1920s. Although it is quite different in style from its neighbors, it fits harmoniously by sharing the same setback and similar height.

A backstreet grocery that is currently functioning as a backstreet grocery—an unusual phenomenon in city neighborhoods these days. The apartment building above it has some interesting and attractive brickwork.