This is a long item, but Father Pitt trusts that no excuse is needed: it is a detailed description of the city of Pittsburgh as it appeared when the author visited the place 205 years ago in 1815. It comes from a book by William Darby published in 1818 and entitled The Emigrant’s Guide to the Western and Southwestern States and Territories.

PITTSBURG is in every respect the principal town, not only of the Ohio valley, but, New-Orleans excepted, of the whole waters of the Mississippi. It was created a city by the legislature of Pennsylvania, at the session of 1815–16. Travellers are almost always disappointed on entering this city; there is but one point of approach that affords a good view of the place; that is the apex of the coal hill, in the road from Washington in Pennsylvania. The city is built upon the peninsula between the Aleghany and Monongahela rivers; the ground plan is nearly in form of a triangle. The bottom upon which the town of Pittsburg was originally laid out, is now nearly filled with houses; a suburb has been laid out upon the Aleghany called the northern liberties, and another upon the Monongahela. The former, from the width of the bottom from the river to the hill, and from the circumstance of the turnpike road srom the eastward entering through it, is extending rapidly; the suburb upon the Monongahela cannot increase considerably for want of room between Ayres hill and the river.

There are four other villages, however, that are virtually suburbs of Pittsburg; Birmingham, upon the left bank of Monongahela, opposite Ayres hill; Aleghany, upon a fine second bottom of that stream, opposite Pittsburg; Lawrenceville, two miles above Pittsburg, upon the same side of the Aleghany; and a street running along the left bank of Monongahela, opposite Pittsburg. When this city and vicinity was surveyed by the author of this treatise, in October, 1815, there were in Pittsburg 960 dwelling houses, and in the suburbs, villages, and immediate outskirts, about 300 more, making in all 1260, and including inhabitants, workmen in the manufactories, and labourers, upwards of 12,000 inhabitants.

This city is literally a work-shop, and a warehouse for the immense country below, upon the Ohio and other rivers. On a cursory survey, when viewing the iron foundries, glass-houses, and other creative machinery, it is not easy to imagine where the products can be disposed of; but a review of the emigration over the mountains will soon remove this wonder. It will be useless to load the pages of this treatise with the names of the various owners of machinery, but a recapitulation of the objects of human wants must be interesting to every emigrant who intends to visit this real phenomenon.

A large steam grist mill, capable of grinding into flour sixty thousand bushels of wheat annually. Three breweries, in which are made an immense quantity of beer, porter, and ale. One nail factory, including the manufacture of many other objects, in which are manufactured nearly 80,000 dollars worth of ironmongery annually. Two extensive air foundries, in which are cast excellent cannon and cannon balls, smiths’ anvils, sad irons, stoves, pots and kettles of all kinds, sugar boilers and cylinders cast, and the latter turned.

Of ironmongery, are now made, sheet iron, nails and nail rods, shovels, tongs, axes, mattocks, hoes, adzes, drawing knives, cutting knives, vices, scale beams, plain bits, chisels, spades, and, in fine, every object necessary in a country of this kind.

Locks, hinges, hasps, screws, but-hinges, bridle bits, buckles, and stirrup and saddle irons, are all manufactured. Waggons, carts, and drays, with every single substance that can enter their composition, and every tool, (perhaps saws excepted) necessary to their construction, are made in this city.

In November, 1815, there were neither coach or harness maker in the city; if that is still the case, an excellent opportunity is offered to any person acquainted with either or both those occupations.

Perhaps of all the wonders of Pittsburg, the greatest is the glass factories. About twenty years have elapsed since the first glass-house was erected in that town, and at this moment every kind of glass, from a porter bottle or window pane, to the most elegant cut crystal glass, are now manufactured. There are four large glass-houses, in which are now manufactured, at least, to the amount of 200,000 dollars annually.

Pottery is carried on in Birmingham, where excellent stone and black ware are made; common red ware is also manufactured to great amount.

To the above may be added, white lead, red lead, buttons, wheel irons, knitting needles, silver plating, stocking weaving, suspenders, boots, shoes, hats, saddles, bridles, bells, stills, copper kettles, brushes of every kind, curry combs, trunks, brass and iron candlesticks, and in fact an infinity of objects of daily demand, brought a few years past from Europe.

Cotton and woollen cloth is also made extensively, consisting of blankets, vest patterns, hosiery, coarse and fine cottonade, and broadcloth.

Except the gratifying reflection arising from the review of so much plastic industry, Pittsburg is by no means a pleasant city to a stranger. The constant volumes of smoke preserve the atmosphere in a continued cloud of coal dust. In October, 1815, by a reduced calculation, at least 2000 bushels of that fuel was consumed daily, on a space of about two and a quarter square miles. To this is added a scene of activity, that reminds the spectator that he is within a commercial port, though 300 miles from the sea.

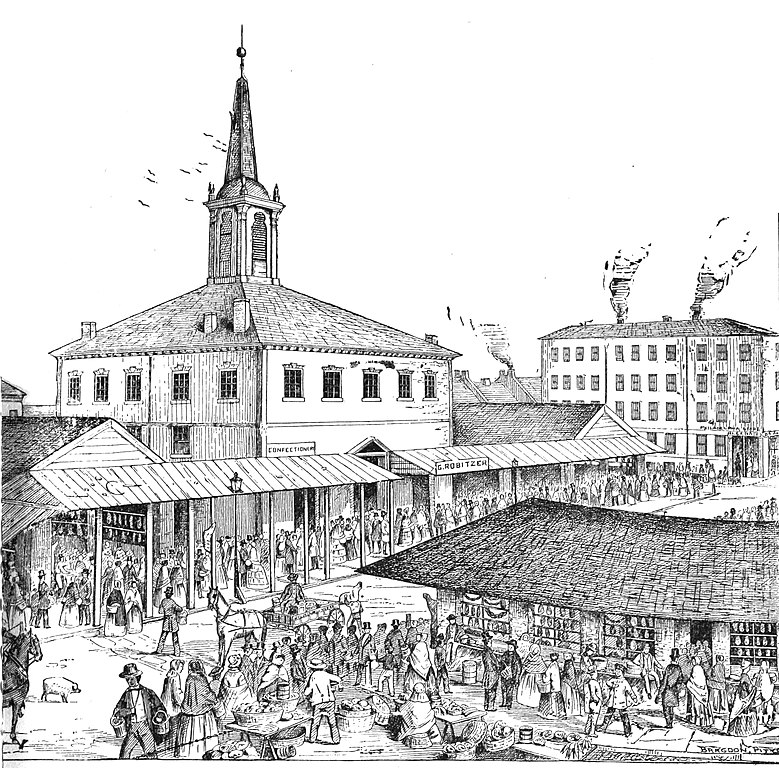

Several good inns, and many good taverns, are scattered over the city; but often, from the influx of strangers, ready accommodation is found difficult to procure. Provisions of every kind abounds; two markets are held weekly.

The circumstance which has contributed most, after its relative position, to secure the prosperity of Pittsburg, is the enormous mass of mineral coal, that exists in its vicinity. The coal, like all other fossil bodies in the Ohio valley, rests in horizontal strata, about three and a half feet thick, of very pure bituminous coal. The strata are 340 feet above low water level, or about 290 above the level of Pittsburg; consequently a falling body from the moment of issuing from the mouth of the mine, until placed in the cellar of the consumer. The medium price, six and a quarter cents per bushel, or two dollars and twenty-five cents per chaldron.

Coal abounds in every hill which rises more than four hundred feet above low water mark: where less than eighty or one hundred feet of incumbent earth rests upon the coal bed, the quality of the mineral is found greatly depreciated. It has been already noticed, that the coal strata are perfectly level with each other. In the neighbourhood of Pittsburg they are divided into three separate bodies; the first, and perhaps most extensive, is west of the Monongahela, the second, on the peninsula upon which the city stands, and thirdly, northwest of the Aleghany river. The supply of the city is taken principally from the beds of the second repository, though an immense quantity is also brought from the first.

Two bridges are, by an act of the state legislature, to be built over the Monongahela and Aleghany rivers, in places best calculated to facilitate intercourse with the adjacent country, and to unite together the scattered and detached fragments of the same commercial community.