The top of Penn Station seen from the Bigelow Boulevard bridge over the Crosstown Boulevard.

Comments

The top of Penn Station seen from the Bigelow Boulevard bridge over the Crosstown Boulevard.

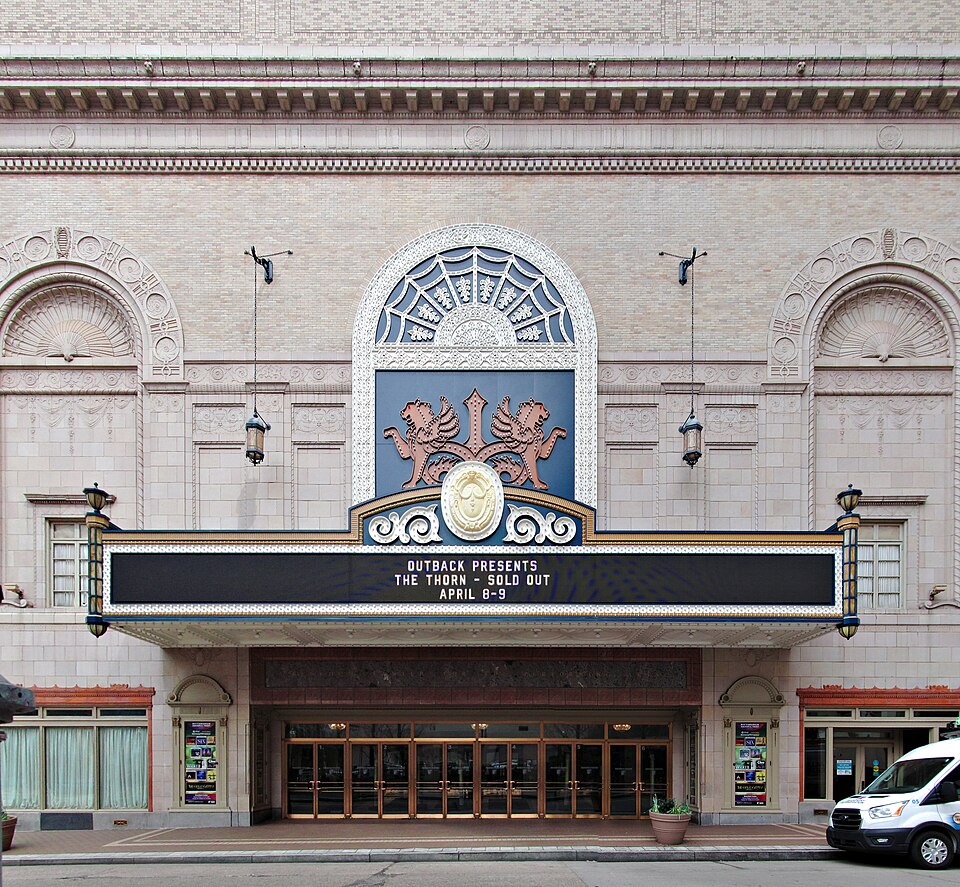

The Stanley was designed as a silent-movie palace, but opened in 1928, just as talkies were making a revolution in the movie business. The architects were the Hoffman-Henon Company of Philadelphia. It was the biggest theater in Pittsburgh when it opened, and as the Benedum Center for the Performing Arts it is still our biggest theater now.

The skyscraper behind the theater is the Clark Building, which was built at the same time and designed by the same architects as part of the same development package.

More pictures of the Stanley Theater.

Following the example of Montreal, Pittsburgh had each of its subway stations decorated by a different artist. The neon installation in Steel Plaza, called “River of Light,” is by Jane Haskell.

The style of the station itself combines Brutalism with Postmodernism.

Trolley Number One, the very first car in the sequential numbering of current Pittsburgh trolleys.

Charles Bickel designed the May Building, and—as he often did—he made liberal use of terra cotta in the ornaments.

More pictures of the May Building.

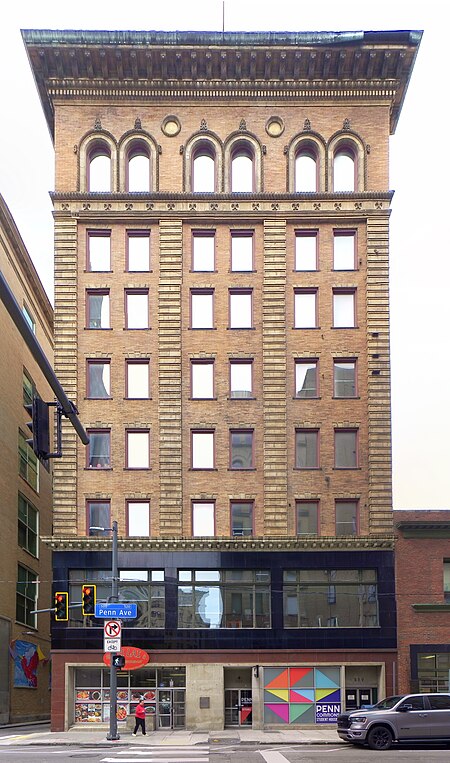

Poe’s “Purloined Letter” taught us that the best place to hide something is in plain sight. Here is a building that has been sitting here on Penn Avenue for more than a century and a quarter, where thousands walk past it every day, but the biographer of Alden & Harlow was unable to find it when she looked for it.

That, of course, is because she was looking for it. Father Pitt almost never finds things when he looks for them. He finds them when he is looking for something else. In this case, our frequent correspondent, the architect and historian David Schwing, had sent an article about the many buildings under construction in late 1896, and among them was this little item:

The Henry Phipps’ store building, on Penn avenue, corner Cecil way, to be finished January 1, is a massive steel structure 60×120, with Pompeiian brick front, ornamented with stone and terra cotta, thoroughly fireproof in construction; will be heated by steam; supplied with an independent electric plant of its own; electric elevators, and lighted by both systems of arc and incandescent. Alden & Harlow, architects.

There is little doubt about the identification. The Phipps-McElveen Building stands on the corner of Penn Avenue and Cecil Way—the corner that plat maps show belonged to Henry Phipps. The plat maps also show that the front of the building is sixty feet wide.

This building does not appear in the gorgeous book Architecture After Richardson by Margaret Henderson Floyd, which exhaustively catalogues all the known buildings of Alden & Harlow (and Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, and the other variations of the firm). However, there is a building that the author could not account for: an “as yet unlocated hotel for L. C. Phipps.” Lawrence C. Phipps was a nephew of Henry who would move to Denver in 1901 and go into the senatorial business. “The brick and terra cotta hotel for L. C. Phipps was eight stories high,” says the book, “but no visual records have been found.”

The brick and terra cotta Phipps-McElveen building has eight floors.

Thanks to the research of Mr. Schwing, who often does find things when he looks for them, we can put together what happened. It appears as though the plans for the property changed more than once. In the middle of 1895, it was announced that a twelve-storey hotel would be built on Penn Avenue from plans by D. H. Burnham & Company. But by early 1896, the hotel plan had been abandoned. “Longfellow, Alden & Harlow have the bids for the erection of an eight-story storeroom building on Penn Avenue, for Henry Phipps, between Marshell’s store and Cecil alley. It was the intention to put up a large hotel on the site, but this scheme has been abandoned. Work had started by early June. During the construction, Longfellow, Alden & Harlow decided to divide their firm, with Mr. Longfellow staying in Boston and Alden & Harlow taking all the Pittsburgh work.

So it looks as though we’ve found the missing building that Margaret Henderson Floyd couldn’t find, and old Pa Pitt offers this visual record in humble appreciation of her meticulous research and engaging writing.

Now the Drury Plaza Hotel, this is a splendid example of the far Art Deco end of the style old Pa Pitt calls American Fascist. The original 1931 building, above, was designed by the Cleveland firm of Walker & Weeks, with Hornbostel & Wood as “consulting architects.” It is never clear in the career of Henry Hornbostel how far his “consulting” went: on the City-County Building, for example, “consulting” meant that Hornbostel actually came up with the design, but Edward Lee was given the credit for it; we would not know that Hornbostel drew the plans if Lee himself had not told us.

At any rate, the lively design almost seems like a rebuke to the sternly Fascist Federal Courthouse across the street, which was built at about the same time.

The aluminum sculpture and ornament is by Henry Hering.

An addition in a similar style looks cheap beside the original; perhaps it would have been better just to admit that the original could not be duplicated and to build the addition in a different style.

Altenhof & Bown, a Pittsburgh firm that also designed the State Office Building, were the architects of what is now officially called the William S. Moorhead Federal Building. It’s a good example of mid-century modern architecture—distinctive in its vertical-blind curtain of aluminum panels, yet somehow easy to ignore.

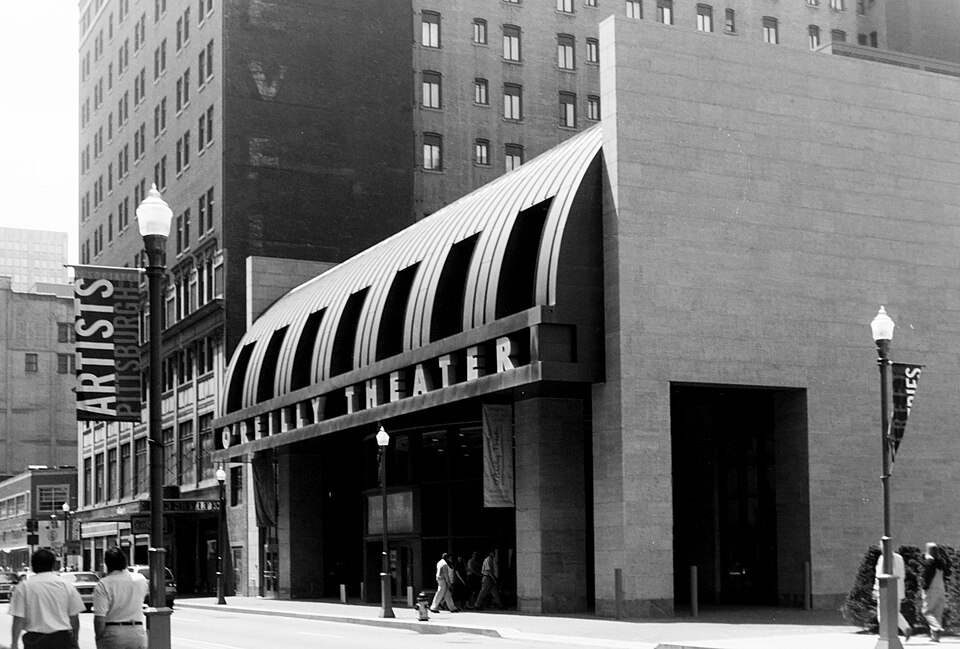

A quarter-century ago, the O’Reilly opened with a brand-new play by August Wilson (King Hedley II). That makes it a newcomer by Penn Avenue standards. But Penn Avenue has been the heart of the theater district for a century and a half, and the O’Reilly stands on the exact site of Library Hall, whose auditorium was used as the Bijou, Victorian Pittsburgh’s most prestigious theater, where touring stars like Dion Boucicault played. The site had been a parking lot for more than sixty years before the O’Reilly was built, but we can think of this theater as continuing the Bijou tradition.

The building was designed by Michael Graves, the postmodernist whose brand of neoneoclassicism was influential in the movement. Mr. Graves also designed Theater Square next door, which houses the Greer Cabaret and a well-dressed parking garage.

Old Pa Pitt has been dumping quite a load of pictures in these pages for the past few days. He realized that the pictures have been backing up and decided he ought to try to catch up with them. But how backed up were they? Here is a picture of the O’Reilly taken with a Kodak Signet 40 in June of 2000, when the building was only six months old. Father Pitt has never published it here before.