Dianthus barbatus naturalized on a bank in Mt. Lebanon Park.

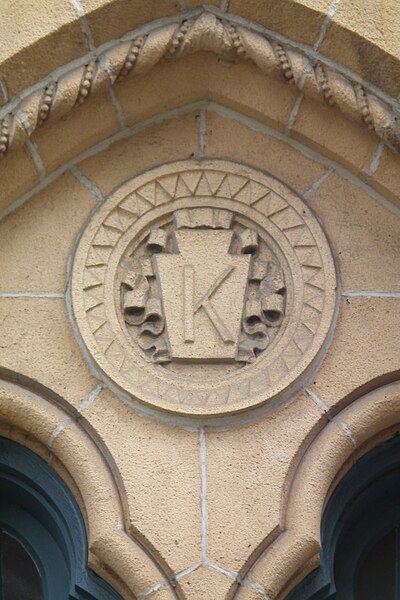

The Keystone Athletic Club was designed by Benno Janssen, Pittsburgh’s favorite architect for high-class clubs of all sorts. Most of them were classical in style, but for this skyscraper clubhouse Janssen chose a simple and streamlined Gothic style instead. It is now Lawrence Hall, the main building of Point Park University, so that two universities in Pittsburgh have trademark Gothic skyscrapers.

Early in his career, Benno Janssen was a fiend for terra cotta; he was much more restrained later on, but he usually included some characteristically appropriate terra-cotta ornaments.

All the older schools in Mount Lebanon were designed by Ingham & Boyd, and here we see a fine example of their style. An Ingham & Boyd school is an implied guarantee that your children will grow up to be respectable citizens. The buildings are in a restrained classical style, with just enough ornament to show that good money was spent on this structure. This particular school is named for a poet who was a big deal in the early twentieth century and has been almost completely forgotten since then.

The far end of Manchester still has some work to do. A few houses have been restored; about an equal number are abandoned and condemned. A few have been restored, and then abandoned and condemned. A few have been renovated in a way that seems regrettable. We can only hope that someone will rescue the houses that need rescuing.

It is always especially sad when we see that the last thing residents were able to do to their house was decorate it for Christmas.

Here we have a frame house refurbished to be habitable and comfortable. “Multipane” windows were used, of course, because is there any other kind? (Old Pa Pitt was shocked to visit a house with modern “multipane” windows and discover that the “panes” are really just cartoon lines drawn in plastic across a single sheet of glass.)

This house suffered a fire years ago and appears to have been abandoned since then. At least some minimal work has been done to stabilize it. The dormer is distinctive; it would have been more so with its original decorative woodwork.

We find some of the houses in better shape as we approach the western end of the street.

Sunset Hills is a Mount Lebanon plan developed in the 1920s and 1930s. Most of the houses are more modest than the ones in Mission Hills or Beverly Heights. Many of them, however, are fine designs by their architects, and in particular several are among the best examples of the Spanish Mission style in Pittsburgh.

Does your garden shed match the architecture of your house? And does it have two floors?

This house is almost a traditional Pennsylvania farmhouse, but with Mission arched porch and stucco.

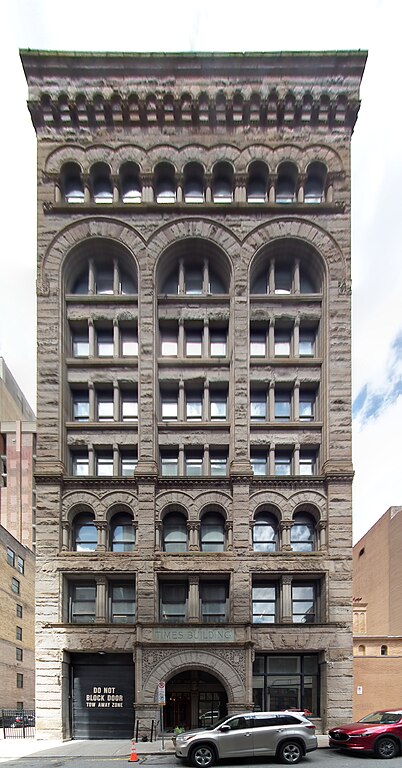

The Times Building, designed by Frederick Osterling in his Richardsonian Romanesque period, is a block deep, so it has fronts on both Fourth Avenue and Third Avenue. The Fourth Avenue front is narrower; the Third Avenue front has one more bay, and a single grand arch in the middle. The decorative carving is probably by Achille Giammartini, who is known to have worked with Osterling on the Marine Bank and the Bell Telephone Building, and all his trademark whimsy is on display here.

This building seems to have been put up for Allen Kirkpatrick & Co., but for years it was the home of the Pittsburgh Tag Co., as this ghost sign tells us. It has been vacant for some time.

The Pittsburgh Tag Company was founded in 1927, as we find in the Paper Trade Journal, December 15, 1927:

Pittsburgh, Pa.—The Pittsburgh Tag Company, care of Charles F. C. Arensberg, 834 Amberson street, Pittsburgh, recently organized with a capital of $50,000, plans the operation of a local plant for the manufacture of paper tags and kindred specialties. Mr. Arensberg will be treasurer of the new company; James M. Graham and Jonathan S. Green will be directors.

The Boylan Building in Beechview, as photographed on February 18, 1930, by a Pittsburgh city photographer.1 We can see that the second floor was an open space useful for all sorts of things—a bowling alley and pool hall, but also dances and basketball games. The barber shop at the left end prominently advertises that it is a UNION SHOP; non-union barber shops were prone to mysterious explosions.

The picture below was taken in 2021 (and nothing substantial has changed since then), so we can see how sensitively this building has been restored for use as a community center. The corner entrance on the left has been filled in, but on the whole the building is pretty much as it was almost a century ago—except that it’s in better shape now.

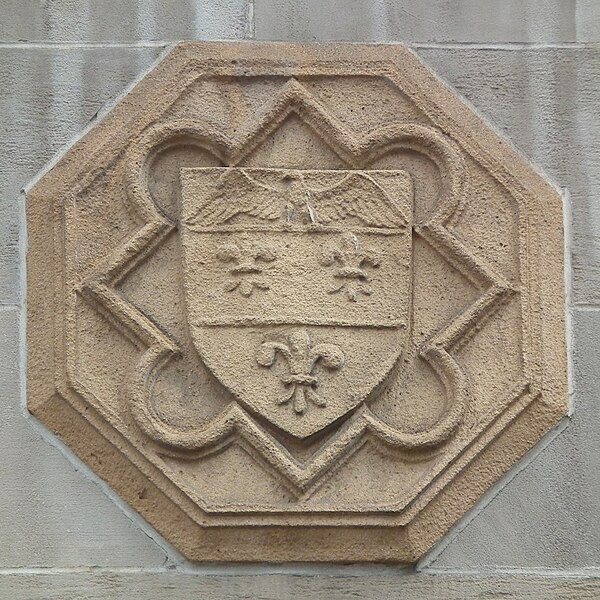

The County Office Building, which opened in 1931, was designed by Stanley L. Roush, who was the king of public works in Allegheny County for a while. Its combination of styles is unique in Pittsburgh, as far as old Pa Pitt knows. In form it is of the school Father Pitt likes to call American Fascist, the weighty classical style filtered through streamlined Art Deco that was popular for American public buildings between the World Wars, and of which the grandest example in Pittsburgh is the federal courthouse. But the details are Romanesque rather than classical—an acknowledgment of the lingering influence of the great Richardson’s greatest masterpiece, the Allegheny County Courthouse. The carved ornaments are Art Deco adaptations of medieval themes, except for the eagle above, which is not at all medieval, and which clasps the arms of Allegheny County in its talons.

The Fourth Avenue side. The County Office Building is roughly square, so the four sides are similar, except that this side lacks an entrance. But this was the side that was lit by the sun when Father Pitt was taking pictures. It took a lot of fiddling and adaptation to get the whole side of the building across a tiny narrow street, so you will see stitching errors and other anomalies if you enlarge the picture.

An Art Deco gargoyle.