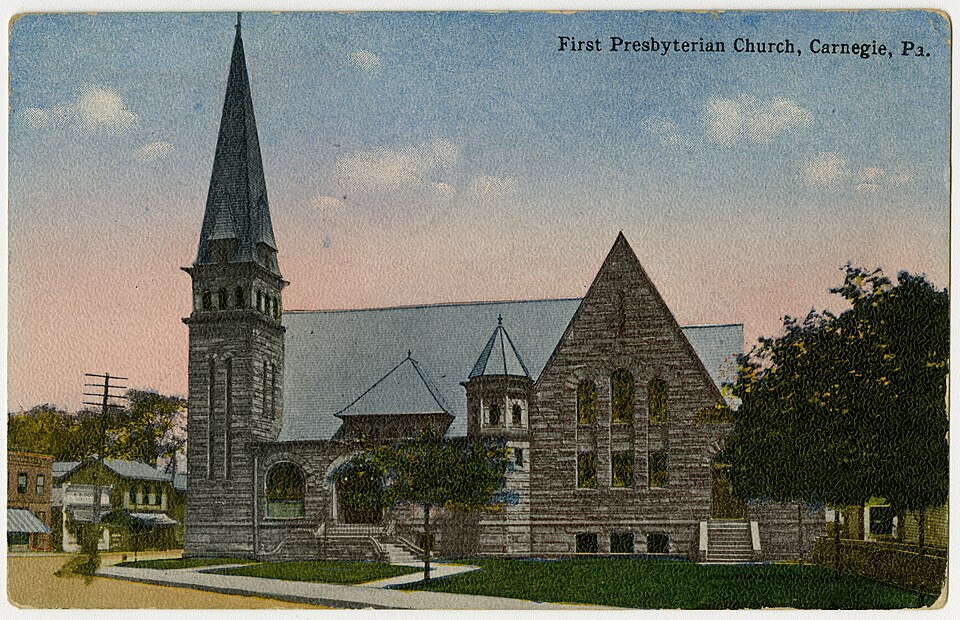

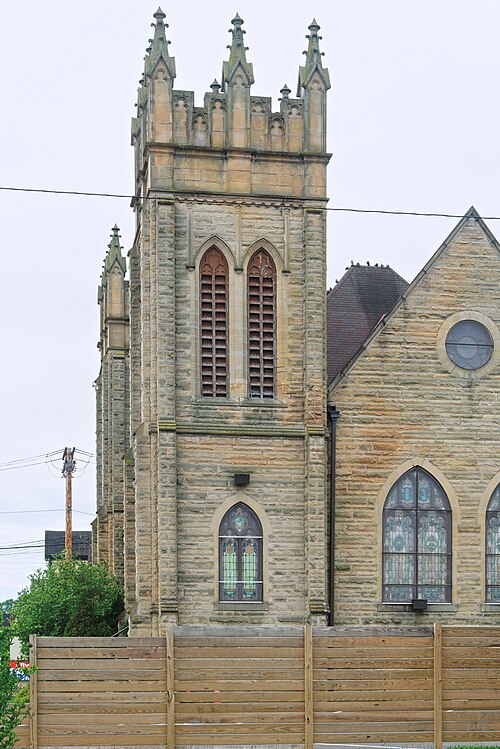

This church, formerly First Presbyterian of Carnegie, now belongs to the Attawheed Islamic Center, which keeps the building up beautifully and lavishes a lot of attention on the landscaping. We can see from an old postcard from the Presbyterian Historical Society collection (undated, but probably about 1900) that this side of the building has hardly changed at all—except for the improvement in the landscaping. Even the stained glass is intact, since it is not representational and therefore causes no offense to Islamic principles.

At least two layers of educational buildings are behind the church.

Diagonally across Washington Avenue is another Presbyterian church…

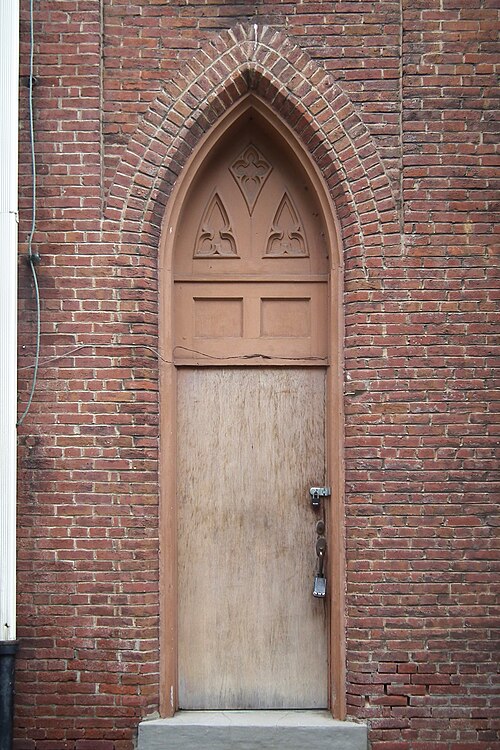

…but this one was First United Presbyterian. The United Presbyterians were a Pittsburgh-based denomination that finally merged with those other Presbyterians in 1958. The building now is used as a banquet hall.

Comments