W. Ward Williams was the architect of this fine hall, built in 1912 for the local lodge of the International Order of Odd Fellows. Like most lodge halls, it was built with the meeting hall upstairs, so that the ground floor could be given over to rent-paying storefronts. The building has been neatly restored and is now home to Community Kitchen Pittsburgh.

The three-link chain is the emblem of the Odd Fellows.

Map.

This striking design was by Janssen & Abbott, and it shows Benno Janssen developing that economy of line old Pa Pitt associates with his best work, in which there are exactly the right number of details to create the effect he wants and no more. The row was built in about 1913.1 The resemblance to another row on King Avenue in Highland Park is so strong that old Pa Pitt attributes that row to Janssen & Abbott as well.

These houses are not quite as well kept as the ones in Highland Park. They have been turned into duplexes and seem to have fallen under separate ownership, resulting in—among other alterations—the tiniest aluminum awnings old Pa Pitt has ever seen up there on the attic dormers of two of the houses.

Nevertheless, the design still overwhelms the miscellaneous alterations and makes this one of the most interesting terraces in Oakland.

The houses in this row at the upper end of 46th Street were all built on the same plan. They were put up in two stages around the turn of the twentieth century, though they are not much different from Pittsburgh rowhouses of a hundred years earlier. The rising value of Lawrenceville real estate has caused an epidemic of third-floor expansions recently; Father Pitt will admit to thinking they are ugly, but by matching the square footage to the value of the location they keep the main structure of the house in good shape. Below we see one house with its original dormer (and classic aluminum awning) and one house with a new third floor (and apologetic little contemporary awningette).

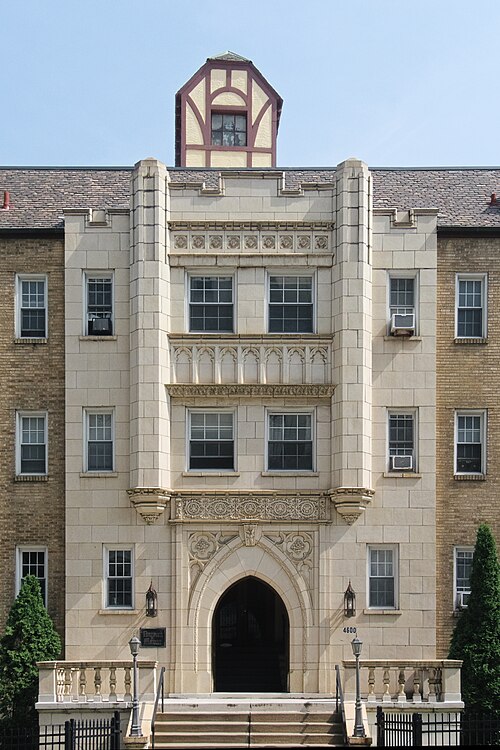

The Bayard Street face of Bayard Manor. Yes, that odd little half-timbered projection on the roof really is skewed in relation to this side of the building. That is because Craig Street and Bayard Street do not meet at exactly a right angle; the roof projection (it probably holds elevator mechanics) is oriented at right angles to every side of the building except the Bayard Street front.

More pictures of the Bayard Street front of Bayard Manor, the main entrance, and the Craig Street side.

Another picture of a Spotted Lanternfly nymph, just because it was posing so decoratively on a ray of Cosmos sulphureus.

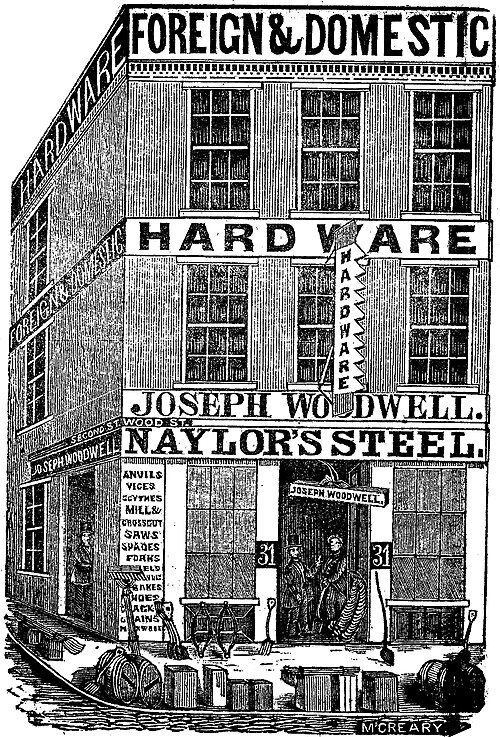

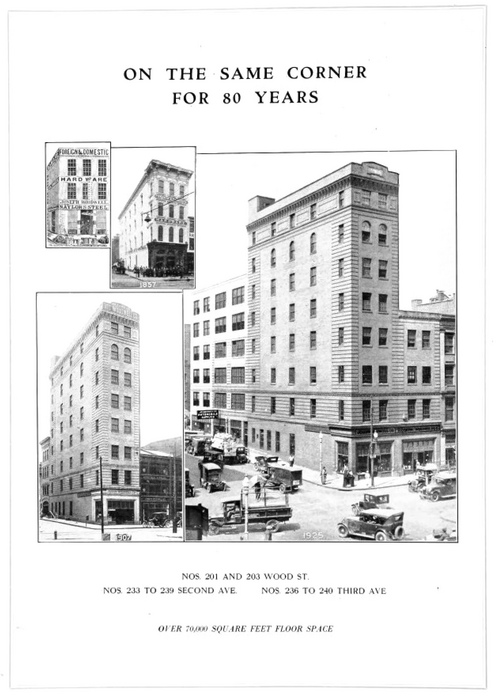

Rutan & Russell designed this building for a hardware company that had already been on this corner—Wood Street and Second Avenue (now the Boulevard of the Allies)—for sixty years when the new building opened in 1907.1 It belongs to Point Park University now, and it is so thoroughly integrated with the buildings around it that most people probably pass it by without noticing it. But it is a unique survivor, as we’ll learn in a moment.

The first Joseph Woodwell hardware store was opened in 1847, and it looked like the engraving above, which was published in Fahnestock’s Pittsburgh Directory for 1850.

A larger building was put up only ten years after the first one, and then this small skyscraper in 1907. Obviously the company was prospering, and it would continue to prosper for quite a while. The frontispiece to a Joseph Woodwell catalogue from 1927 shows us the all the Woodwell buildings up to that date.

You notice the main Woodwell Building in a picture from 1907, and then the same building surrounded by newer construction in 1927. But although it’s the same building, it’s not in the same place.

Until 1920, Second Avenue was a narrow street like First Avenue or Third Avenue—streets that would count as alleys in most American cities. But in 1920, when the Boulevard of the Allies to Oakland was being planned, the city began widening Second Avenue by tearing down all the buildings on the north side of the street.

All but one. The Woodwell Building was not demolished: instead it was moved, all eight floors of it, about forty feet to the right. That makes it the sole surviving complete building on the north side of the street from before the widening project. (The Americus Republican Club survived in a truncated form.) The building gained a four-floor addition (now replaced with a more modern building) to the right on Wood Street, and yet another new building went up for the prospering Woodwell firm behind the relocated building on the Boulevard of the Allies.

So the next time you walk down the Boulevard of the Allies, pause briefly to acknowledge the Woodwell Building. It’s a stubborn survivor as well as an attractive design by one of our top architectural firms, and it has earned some respect.

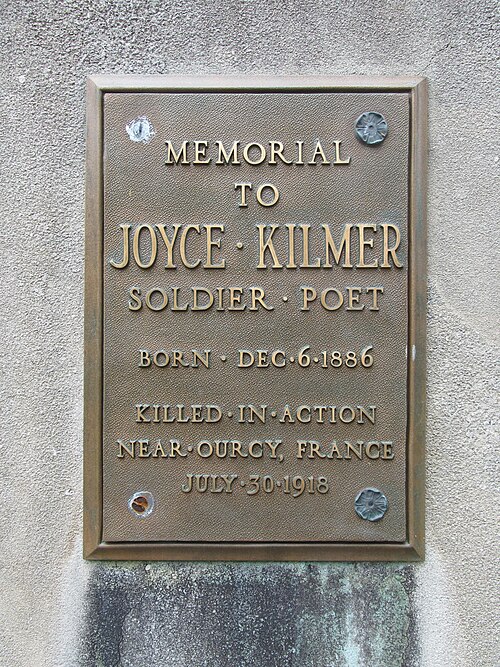

Joyce Kilmer was only 31 when he died in action in the First World War. But he had written one poem that made him immortal: “Trees,” which for two generations was inescapable at school recitations and equally inescapable set to music by Oscar Rasbach, in which form it was performed in every style from amateur opera to Benny Goodman’s swing.

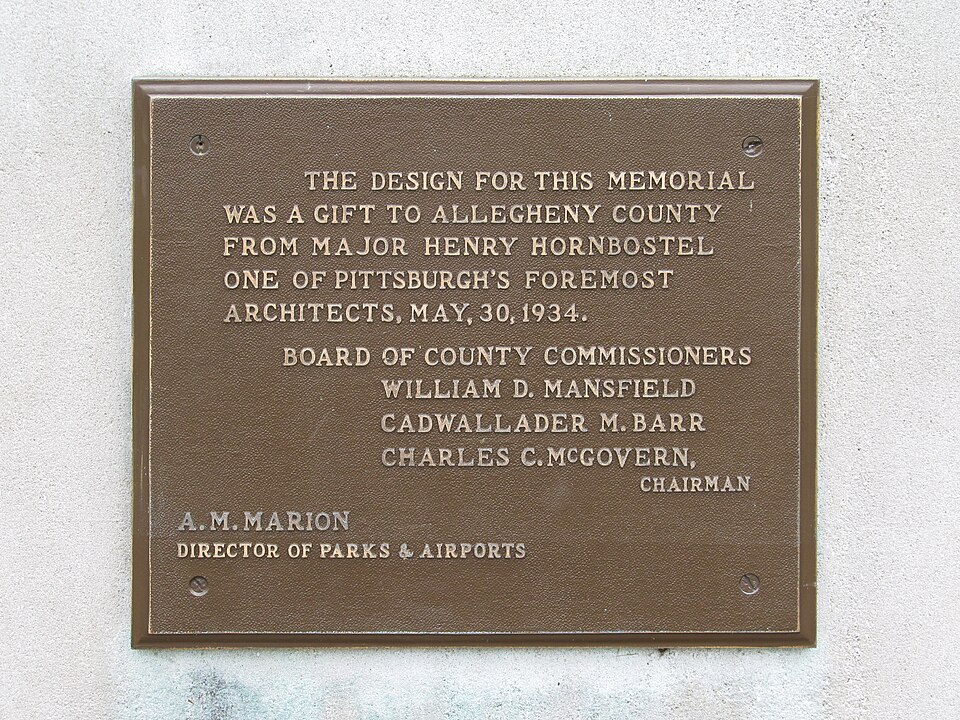

The Joyce Kilmer Memorial in South Park, which sits in the middle of a circle at a prominent intersection, was designed by Henry Hornbostel, who donated his work on the project.

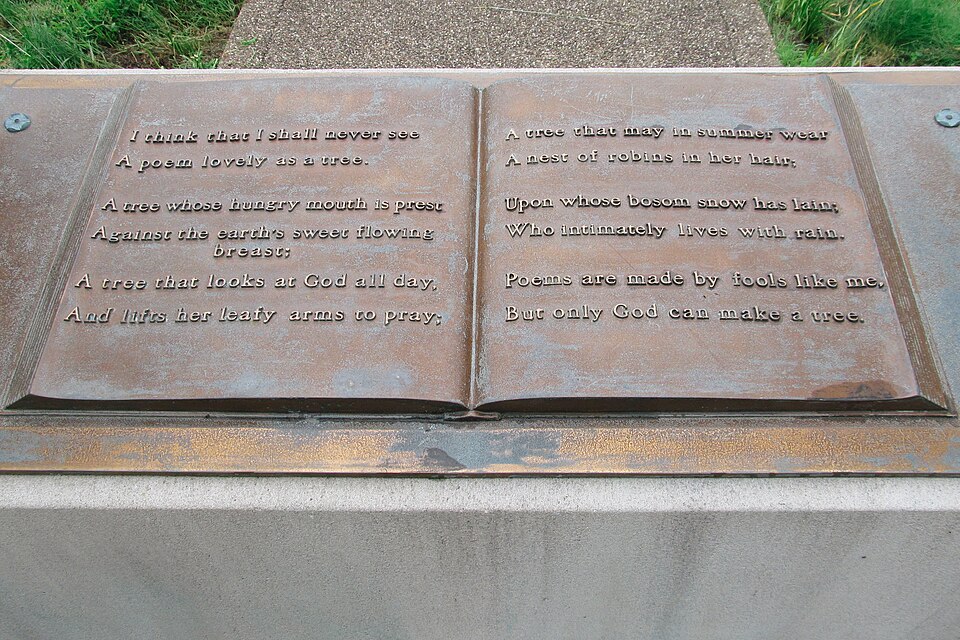

The monument is simple, designed to focus attention on the one thing visitors will really care about: the poem “Trees” itself, inscribed in a bronze book.

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.A tree whose hungry mouth is prest

Against the earth’s sweet flowing breast;A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;A tree that may in summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.Poems are made by fools like me,

But only God can make a tree.

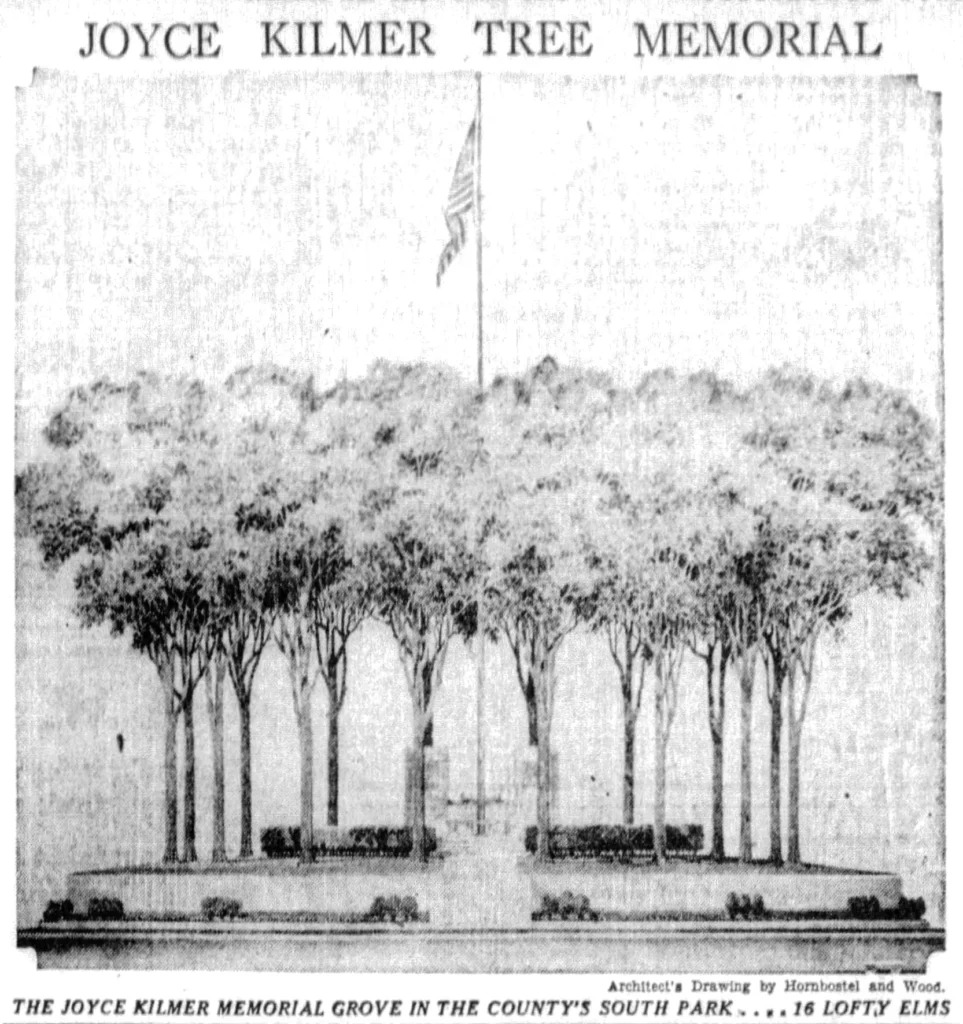

The architectural part of the memorial is in good shape. However, the main part of Hornbostel’s design is missing, as we can see from his drawing published in the Sun-Telegraph.

The memorial was meant to be ringed by trees, the only truly fitting tribute to Kilmer’s legacy. Hornbostel chose elms, and the Dutch elm disease has made merely keeping elms alive a difficult endeavor. The blighted trees were taken down in 1961, and the circle was left almost bare. Other trees have been planted more recently, but the effect will not be the same: his drawing shows that Hornbostel chose elms for their characteristic shape. But at least there will be trees again.

The local historian Jim Hanna has made a short video about the memorial.

Map.

Back in 2014, old Pa Pitt took these pictures of the old St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Munhall. In the intervening years Father Pitt has learned much more about making adjustments to photographs to produce a finished picture that looks like the scene he photographed, so he presents these pictures again, “remastered” (as the recording artists would say) for higher fidelity.

The church was built in 1903 for a Greek Catholic (or Byzantine Catholic, as we would say today) congregation. When Pittsburgh became the seat of a Ruthenian diocese, this became the cathedral.

The mad genius Titus de Bobula, who was only 25 years old when this church was built, was the architect, and this building still causes architectural historians to gush like schoolgirls. It includes some of De Bobula’s trademarks, like the improbably tall and narrow arches in the towers and side windows and the almost cartoonishly weighty stone over the ground-level arches. It’s made up of styles and materials that no normal architect would put together in one building, and it all works. Enlarge the pictures and note the stonework corner crosses in the towers and all along the side, which we suspect were in the mind of John H. Phillips when he designed Holy Ghost Greek Catholic Church in the McKees Rocks Bottoms, which also makes use of De Bobulesque tall and narrow arches.

The rectory was designed by De Bobula at the same time.

This illustration of the church and rectory was published in January of 1920 in The Czechoslovak Review, but it appears from the style to be De Bobula’s own rendering of the buildings, including the people in 1903-vintage (definitely not 1920) costumes.

The Byzantine Catholic Cathedral moved to a modern building in 1993, still in Munhall, and this building now belongs to the Carpatho-Rusyn Society. According to the Web site, the organization is currently doing “extensive renovations,” which we hope will keep the church and rectory standing for years to come.

Built in 1898 for Rowe’s department store, this building has been called the Penn-Highland Building for years now. The architects were Alden & Harlow.

Lions stare back at you from all over the building.