Tiny black bees (probably some species of Chelostoma, but the entomologically inclined are earnestly invited to correct us) enjoying flowers on two slightly different shades of Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa).

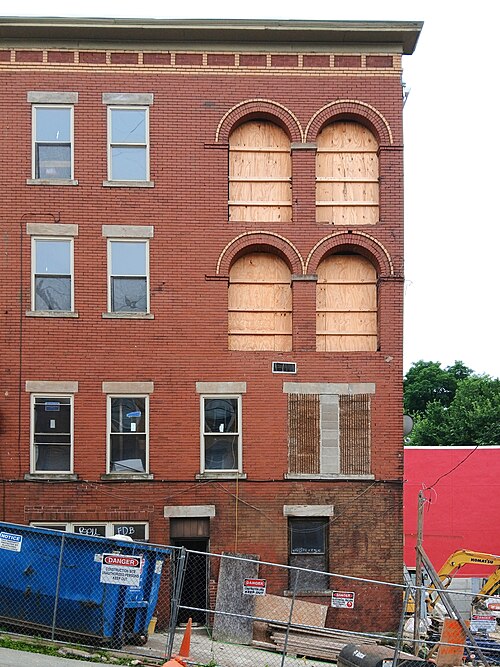

About twenty years ago, there was an aborted attempt to revitalize the business district of Beechview—aborted because the developer absconded with the money and went back to his native Brazil, whence, according to the Brazilian constitution, he could not be extradited. So neighborhood gossip tells us, at any rate. The project had got as far as partly restoring this building, and a thriving restaurant occupied the ground floor for a while. But then the furnace broke, and the landlord was gone, and the building was tied up in legal wrangling and became uninhabitable. Meanwhile, much of the business district more or less revitalized itself, with a big Mexican supermarket and a number of interesting ethnic restaurants moving in.

Now, at last, the restoration is beginning again, and this time it seems very thorough. It’s an attractive building that deserves a long future. Old Pa Pitt hopes his readers will pardon these hasty cell-phone pictures, taken as he happened to be passing by without his usual big bag of cameras.

Although Father Pitt has no evidence other than the style and the location, he suspects the building was designed and built by local architect and contractor William J. Gray, who was responsible for the Boylan Building on the opposite corner of the same intersection and for a now-vanished building on one of the other corners—and quite possibly for the building on the fourth corner as well.

These arches framed inset balconies for the upstairs apartments. It looks as though they are to be filled in, which may be necessary to make the building rentable, but will take away a distinctive feature.

The French Flag flying for Bastille Day, but the buff Kittanning brick tells you it’s flying in Pittsburgh. Bastille Day comes just ten days after our Independence Day, and it’s a good day to remember that Pittsburgh was French before it was English, and that there would be no United States of America without Lafayette, de Grasse, and the other French heroes of our revolution.

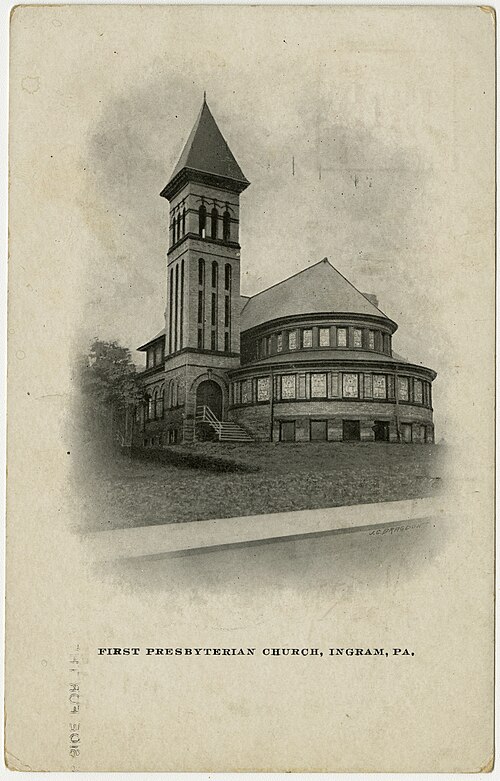

Built in about 1898, this church was designed by James N. Campbell,1 and it displays all the usual quirks of his style, including the corner tower with tall, narrow arches and the half-round auditorium made into the most prominent feature of the building: compare, for example, Beth-Eden Baptist Church in Manchester. It has been a Masonic hall for quite a while now. There are, however, still Presbyterians right across the street: the First United Presbyterian congregation was there, and the two denominations merged in 1959.

In this case the Masons have not blocked in most of the windows the way men’s clubs usually do when they take over a building. An old postcard from the Presbyterian Historical Society collection shows that the basement windows have been filled with glass block, and the open tower has been bricked in. But the stained glass is still intact through most of the church.

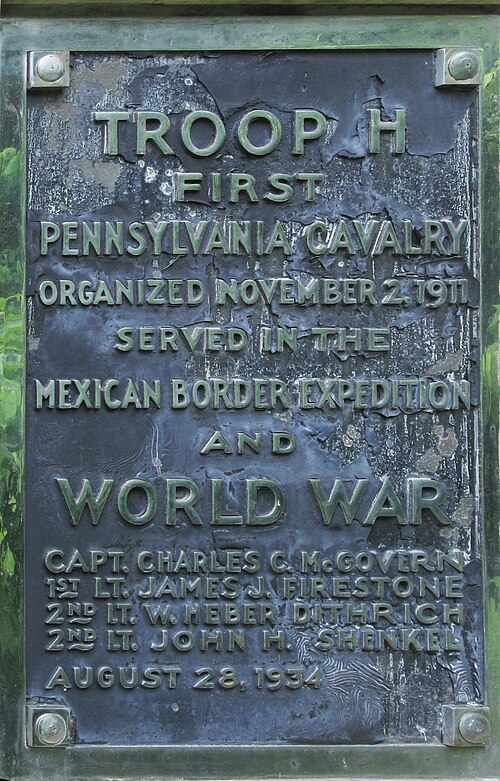

Instead of a heroic soldier, or—as in more than one First World War memorial—a baffled and scared soldier, we have a shiny plaque with a horse all ready for a rider. This strikes old Pa Pitt as a real soldier’s monument. A member of Troop H would remember the horses above all as what distinguished a cavalry unit. He would look at this relief and feel immediately that he was the soldier who was meant to mount that horse. In a way, the monument also serves as a memorial to the passing away of the horse as an important factor in military operations.

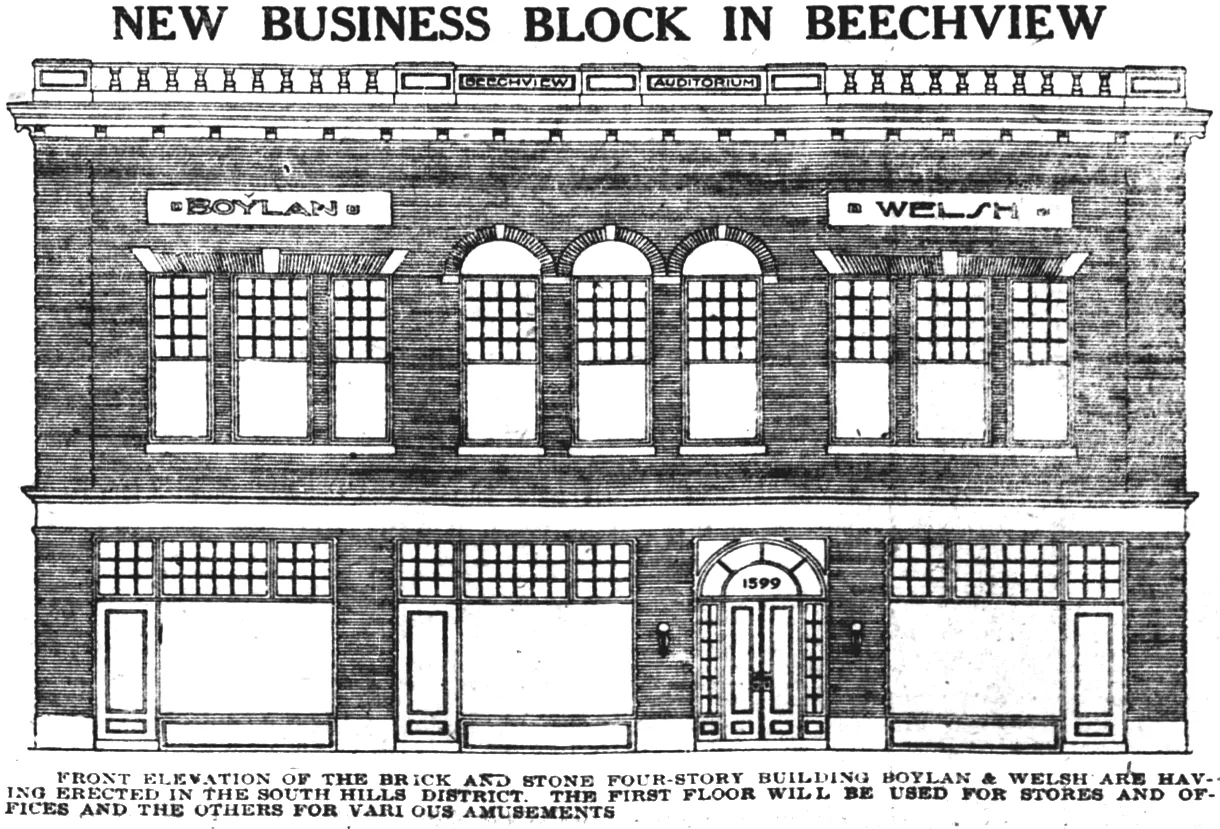

This elevation appeared in the Pittsburg Press (a paper that left the H off “Pittsburgh” until 1921) on December 4, 1910. The building went up shortly afterward and opened in 1911; by the time it was open, or shortly after, it was known as the Boylan Building. (Old Pa Pitt doesn’t know what happened to Welsh.)

The architect and contractor was William J. Gray, who was so local that his address was literally across the street. Gray worked on several buildings in the Beechview commercial district, and he designed some of Beechview’s better houses as well. When this building was finished, he moved his office into it, and it would have given prospective clients a favorable impression. The building is now beautifully restored as the Beechview Community Center.

We do not know whether the Renaissance parapet in the drawing was ever built. The high-ceilinged hall upstairs was used for pool, bowling, dancing, and other “amusements,” as we see in this picture from 1930 by a Pittsburgh city photographer.

If you looked closely at the architect’s elevation above, you might have noticed that it shows a building with two floors, but the caption refers to it as a “four-story building.” Is that a misprint? No; it’s just Pittsburgh.

Broadway in Beechview runs along the crest of a ridge, with steep slopes away from the street; and the upstairs auditorium is as tall as the two floors behind it.

The white facing blocks of this house set it apart from its neighbors, and from most other houses in Pittsburgh. Are they stone? Are they concrete? Well, mostly concrete, but a bit of both.

When the house was going up, it attracted some attention for its novel material. From the Gazette Times, December 20, 1914:

A house nearing completion in Brookline, attracting much attention, is the home being erected by Mrs. Mary M. Otterman, on Berkshire avenue, near Castlegate avenue. Its construction is hollow tile, veneered on the outside with white “marble” blocks. These blocks are made on the premises by the use of a molding machine, the material used being white cement and marble dust. While this method of construction is not expensive, it has a very beautiful effect. The white “marble” walls, with rich brown trim and colored roof, make it one of the most attractive homes in the South Hills. The property is being visited dally by architects, contractors and prospective builders and no doubt many “marble” veneer houses will be built around Pittsburgh in the early spring.

Well, it’s surprising how few of these “marble” houses we do see around Pittsburgh. It may be that architects and contractors missed out on a good idea. Here it is, 111 years later, and the “marble” blocks are still in perfect shape.

Frederick Sauer was probably the architect of these rather German-looking houses. They were built as rental properties on land that belonged to developer John Dimling, and in every case where we have found an architect listed for a Dimling project, it is always Frederick Sauer.

It is a little hard to tell how the right end of the row looked originally. Alterations that look as though they were made in the 1970s have obscured the original design, which—with its curved corner—would have been something interesting.

“God is in the details,” as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe said, and the details that would have refined the style of this double house have been lost: windows have been replaced, a hipped roof (invisible from this angle) replaced the original flat roof about six years ago, and we suspect that the porch railings and aluminum canopies are not original. Even so, we can see enough to see that this was an interestingly modern construction when it went up, probably in the late 1930s or the 1940s. The corner windows were a badge of modernity.

An exceptionally splendid instance of the turn-of-the-twentieth-century interpretation of Georgian architecture from the days when the Colonial Revival was beginning to gather steam.