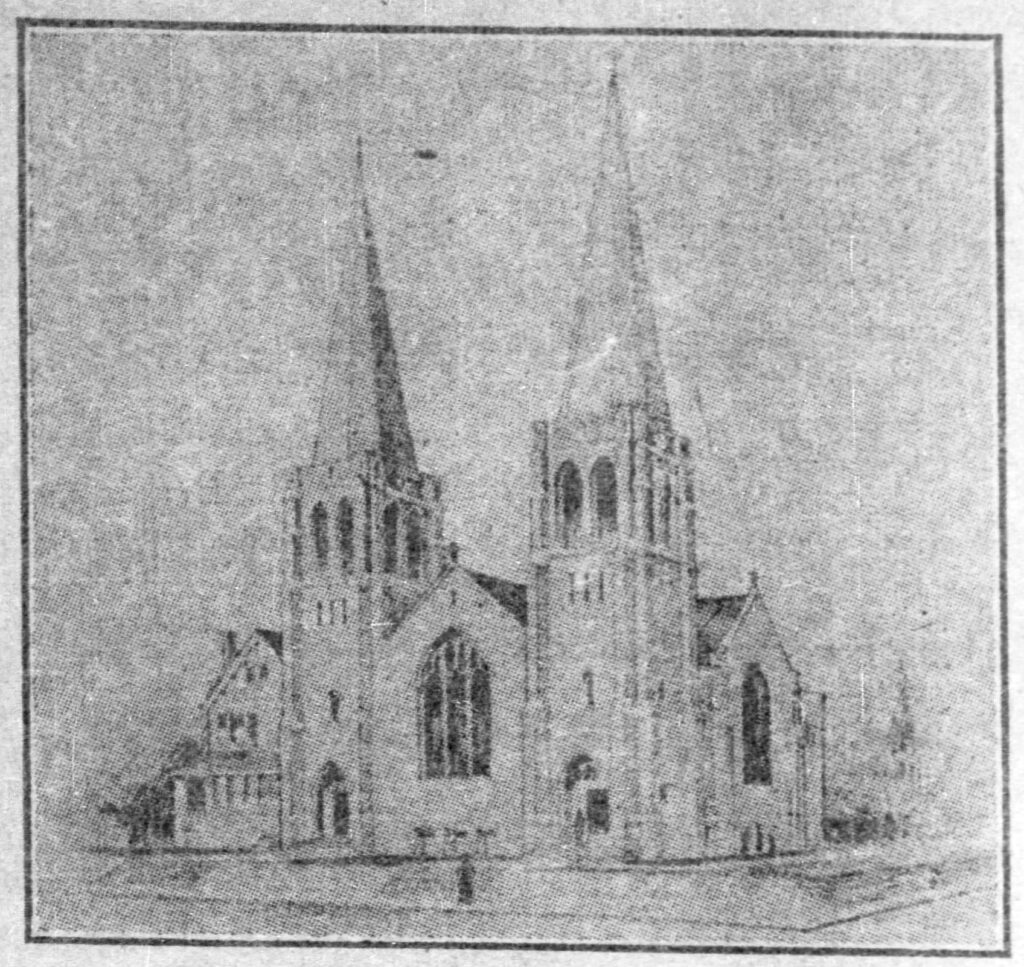

Gustavus Adolphus was a Swedish congregation that began in Lawrenceville, but in 1908 it bought this lot at Evaline Street and Friendship Avenue. O. M. Topp, the favorite architect among Lutherans, was commissioned to design this imposing Gothic building.1

The cornerstone was laid in a howling storm on July 13, 1908,2 and the church was completed in seven months—except for the main auditorium. It seems the congregation ran short of money and worshiped in the basement social room for several years. The main church was finally finished in 1916.

The church is now called Evaline Lutheran, but it is still Lutheran, and its spires still point heavenward—an unusual survival: probably a majority of churches of the era have lost their spires and must be content with bareheaded towers. It also has not been cleaned of its historic soot, making it one of our increasingly rare black stone churches.

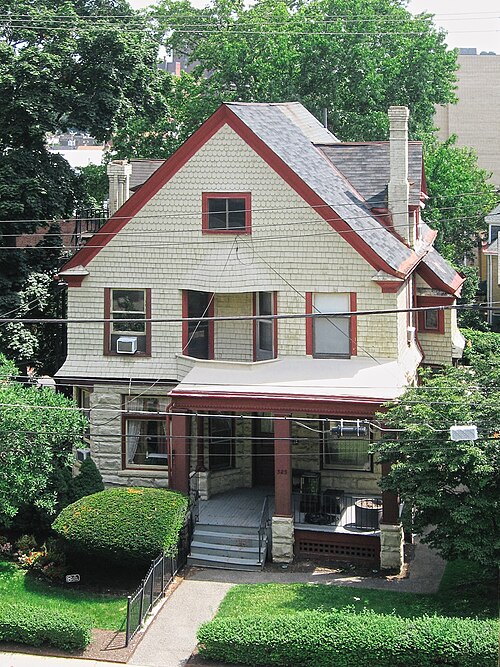

The Tudor-style parsonage next door was also designed by Topp and built at the same time; it was connected with the church through the pastor’s study.

Comments