Update: This article is kept here for historical reasons, but the map here is out of date. For an up-to-date map, see Father Pitt’s latest article on Pittsburgh rapid transit.

—

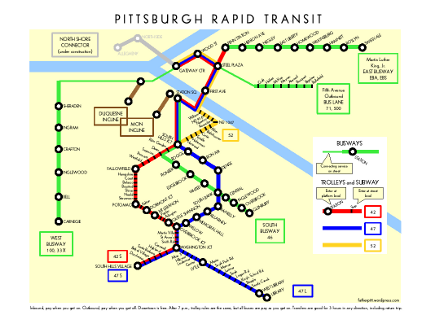

Father Pitt has already offered one map of Pittsburgh rapid transit. That one was meant to show the attractions along the way. This new map is an attempt at a schematic map, somewhat after the manner of the famous London Tube maps, that will fit comfortably on a single sheet of letter-size paper. Old Pa Pitt would not have attempted such a thing if the Port Authority had created a useful rapid-transit system map, but that august body has not done so, instead doling out partial maps in bits and pieces.

This map is an early draft, on which comments are invited.

And now, a few words about Pittsburgh’s rapid-transit system, which old Pa Pitt (who is admittedly prejudiced) thinks is an admirable start, better than almost any other system for a city of this size in the United States.

What is rapid transit, and how does it differ from plain old non-rapid transit? For our purposes, “rapid transit” means what the Port Authority calls “fixed-guideway systems”: that is, anything that has its own dedicated track. In addition to the lines on this map, there are nearly two hundred bus routes that run on the street in ordinary traffic.

Trolleys or streetcars (the terms are interchangeable here) run on rails. The Port Authority calls the cars LRVs, for “light-rail vehicles,” but no one else calls them that. Depending on how you count, there are somewhere from three to six routes.

Route 52 runs almost entirely on the street. Routes 42C and 42S run on the street in Beechview, but on their own right-of-way everywhere else. Routes 47L and 47S run entirely on their own right-of-way. The short spur to Penn Station is served by only two rush-hour cars (Route 42 Penn Park) a day.

Downtown, the cars run in a clean and pleasant subway. Routes 42 and 47 also run underground between Station Square and South Hills Junction, and Route 42 runs underground between Dormont Junction and Mount Lebanon. For reasons old Pa Pitt doesn’t pretend to understand, no one around here calls those other streetcar tunnels subways.

Subway stations, and major stations elsewhere, have high-level platforms on the same level as the floor of the car. Other stops on the lines have street-level platforms (if they have platforms at all). Because of this odd system, Pittsburgh streetcars have to be specially made with entrances at two levels. You can see the two levels plainly in this picture:

The disproportionate rail coverage of the South Hills is an accident of history. When shortsighted bureaucrats were abandoning streetcar lines right and left, the ones that stayed were the ones that had their own right-of-way for most of the route, and those happened to be in the South Hills. The exception is the Allentown Trolley, Route 52, which survives because it makes a vitally useful bypass for the other routes if the transit tunnel under Mount Washington has to be closed for some reason.

Busways in Pittsburgh are not like the half-hearted “bus rapid transit” lines some cities like Cleveland and Boston are installing. They’re more like rubber-tired metro lines. Like a true metro, they are entirely grade-separated, meaning that they never intersect with any cross streets or join with street traffic. Also like a true metro, they stop infrequently and reach high speeds between stops—sixty miles an hour or more. The main difference is that, at the ends of the busway, the giant articulated buses can go on into the streets; most busway routes make a loop downtown.

Father Pitt thinks busways are inferior to rail transit, for the simple reason that no one loves a bus, no matter how quick or convenient. Rail transit attracts more riders. Nevertheless, the busways (which were built with eventual conversion to rail in mind) are efficient and very fast. Pittsburgh invented the busway (the South Busway was the first one in the world, as far as we know), and we got it right the first time.

Inclines are funicular railways that climb steep hillsides. The cars come in pairs attached to a long cable; the weight of one car going down helps pull the other car up. The cars move slowly, but because an incline goes straight up an otherwise impassable hill, it’s the fastest way to get from up to down or down to up.

Pa Pitt debated with himself whether to include the Fifth Avenue bus lane, but eventually decided to keep it. Outbound through Soho and Oakland, the buses travel against the flow of traffic in a lane of their own, so that even in rush hour they move smoothly through the most congested part of the city. And the link to Oakland is so vital that including it markedly increases the utility of the map. The inclusion of the bus lane, however, should not be taken as a sign of old Pa Pitt’s acquiescence in the current state of affairs. Some form of subway, trolley, monorail, maglev, or teleportation between downtown and Oakland is still our highest transit priority.

Leave a Reply